Load balancing is critical to any scalable and highly available cloud application. The obvious choice for load balancing on AWS is ELB, but unfortunately if you require features such as a static IP or URL based request routing then ELB isn’t an option.

HAProxy is a great solution that performs extremely well even on small EC2 instance types. It is also a supported layer type in OpsWorks which makes it the obvious choice for OpsWorks users.

It’s well known that several large application servers can be served by just a single small HAProxy server, but what is the definition of small? How about the smallest EC2 instance on offer - the t2.micro? This blog post puts HAProxy on a t2.micro to the test using loader.io to determine just how many requests/second it can handle and whether CPU or network is the limiting factor.

Method

To create a test environment I set up an OpsWorks stack with a HAProxy and PHP layer. I then deployed the following file:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

This is intended to emulate a fairly typical application request from the perspective of the load balancer (ie. takes about 300ms to generate and the resulting document is about 50kb in size). Having a fixed page generation time is convenient as any increase in the overall response time can be assumed to be due to the load balancer.

I also created a status.php which does nothing but return a 200 response to serve as the health check.

I then launched the following instances:

- 1 x t2.micro to the HAProxy layer

- 4 x c3.large to the PHP App Server layer

At no time during my testing did the application servers show any signs of excessive load, however I wanted to ensure that there was ample excess capacity and that the load balancer would be the bottleneck in my tests.

The only changes I made to the standard OpsWorks configuration was to install NewRelic, and raise the node[:haproxy][:maxcon_factor_php_app] value to 50.

I used loader.io to generate the load and produce these nice graphs.

Results

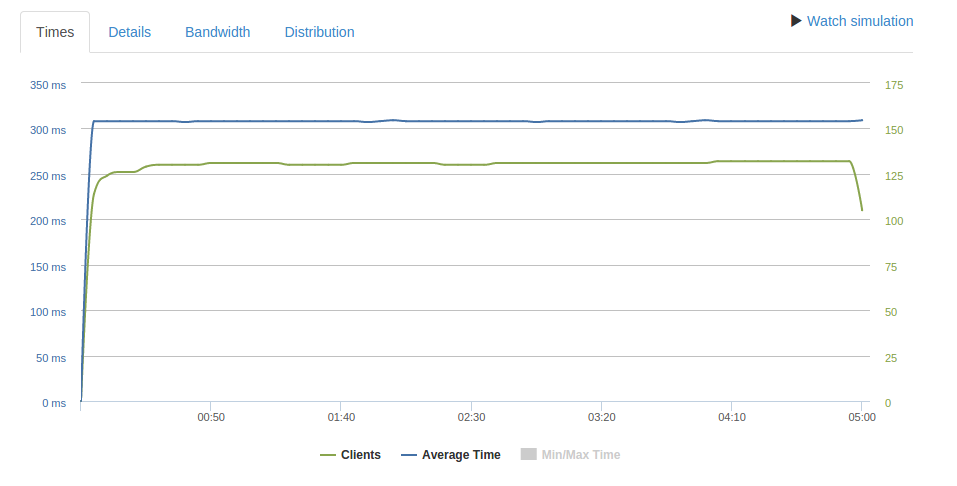

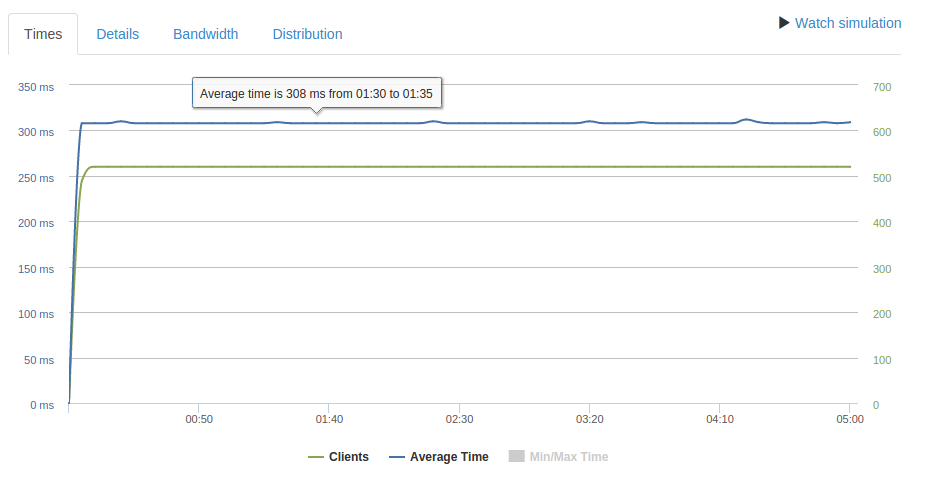

100 req/sec over 5 minutes

Loader.io

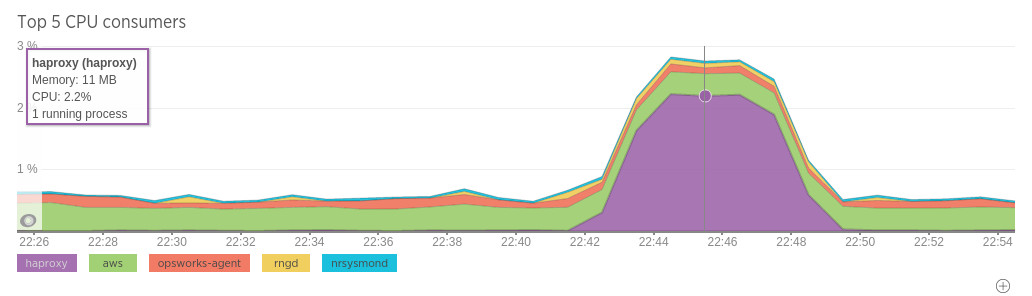

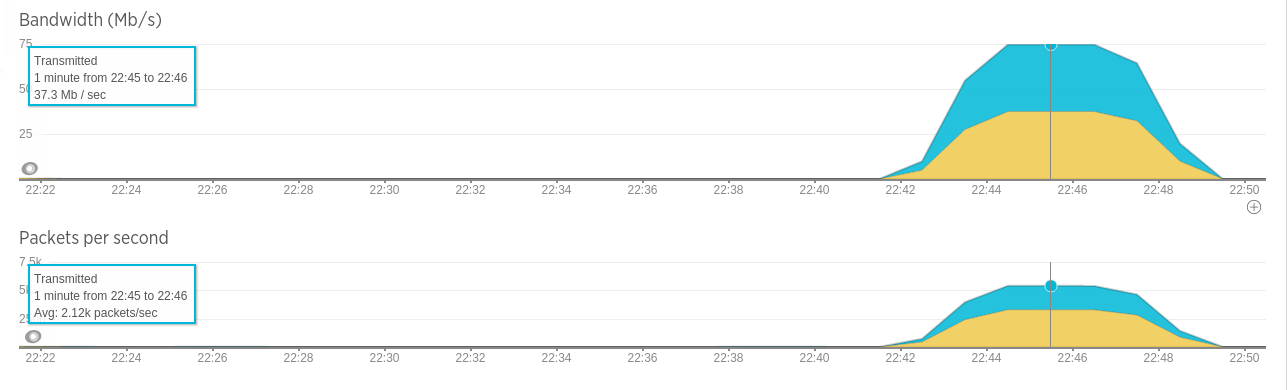

NewRelic

As you can see, at 100 req/second CPU load is less than 2%, although combined network throughput is ~75Mb/s. No requests timeout and response times are stable.

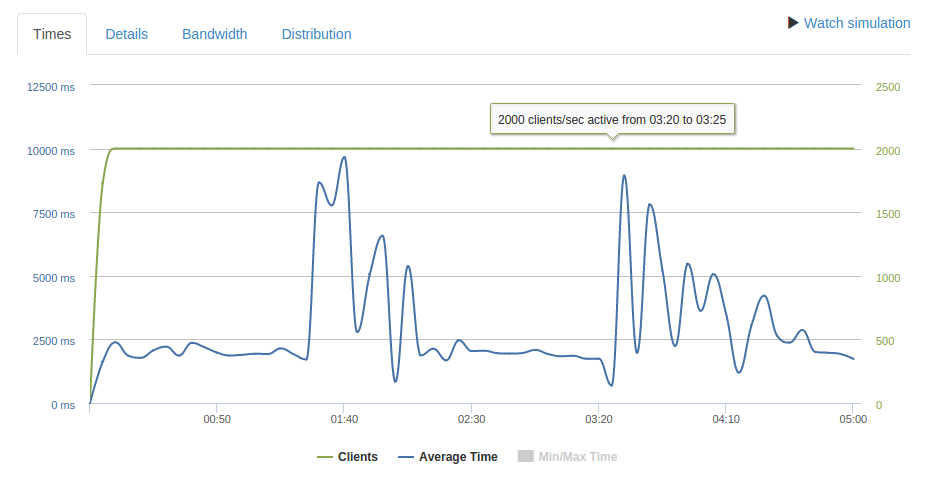

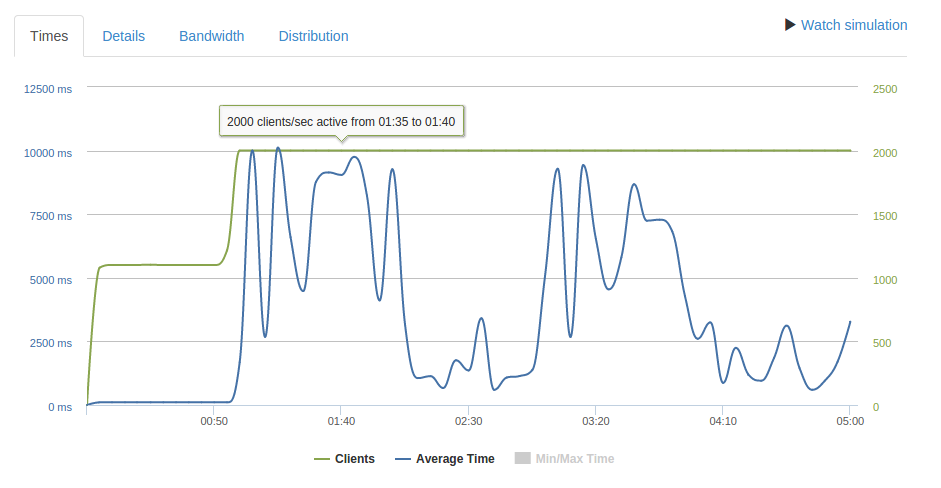

1000 req/sec over 5 minutes

Loader.io

At 1000 req/second performance has definitely degraded. 10521 requests timeout while 157726 succeed and there is significant fluctuation in response times.

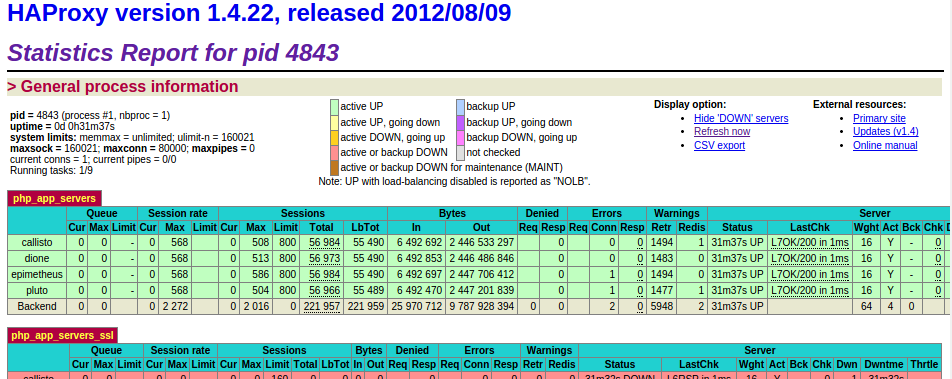

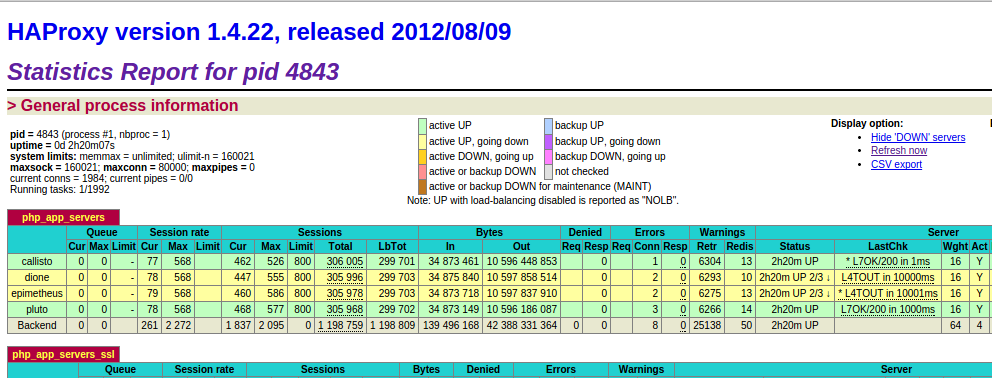

HAProxy stats

The HAProxy stats suggests requests aren’t being queued by HAProxy, and the application servers are barely at 5% CPU.

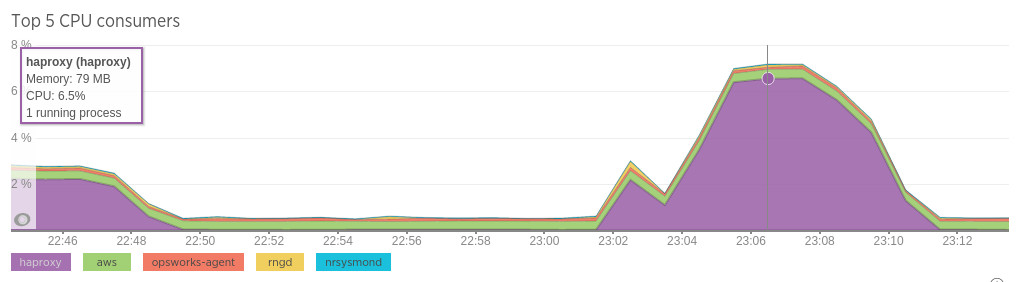

NewRelic

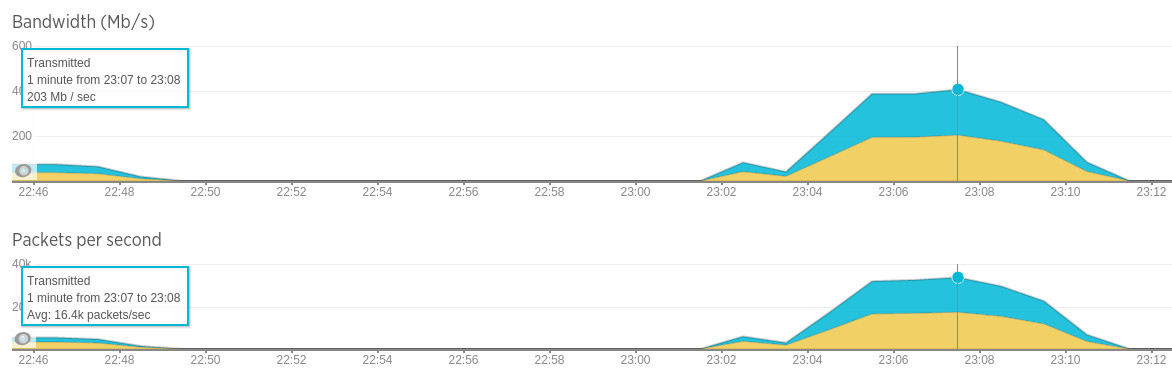

This time CPU is higher, but still only ~7% - however combined network throughput is close to 40k packets/second and 400 MB/s.

Clearly network capacity is the limiting factor.

Finding the limit

Using the previous result it seems conservatively the outbound network capacity limit is about 180 Mb/s. If we assume each

request is about 50 kB the approximate limit should be (180 * 1024 * 1024) / (50 * 1024 * 8) = 460 req/second.

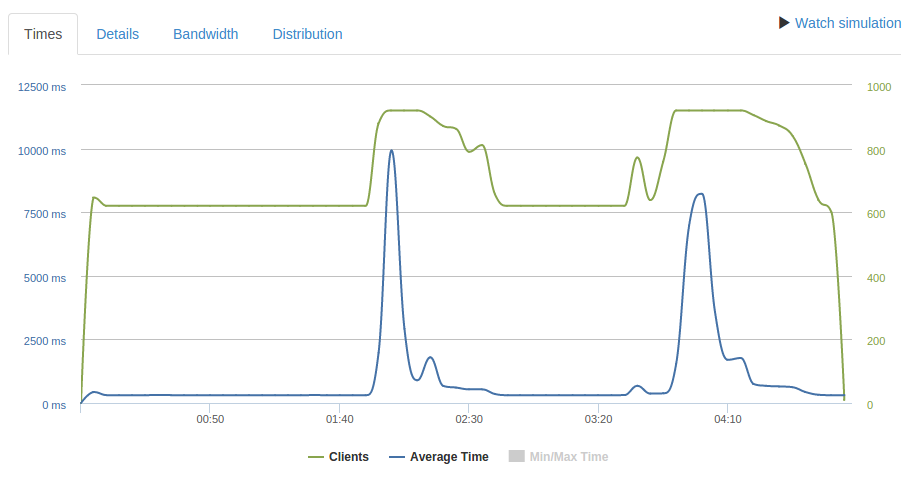

460 req/second

At 460 req/second response times are mostly a flat ~300 ms, except for two spikes. I attribute this to TCP congestion avoidance as the traffic approaches the limit and packets start to get dropped. After dropped packets are detected the clients reduce their transmission rate, but eventually the transmission rate stabilizes again just under the limit. Only 1739 requests timeout and 134918 succeed.

400 req/second

Testing again at 400 req/second which should be well within the limit we can see stable response times with no spikes or timeouts.

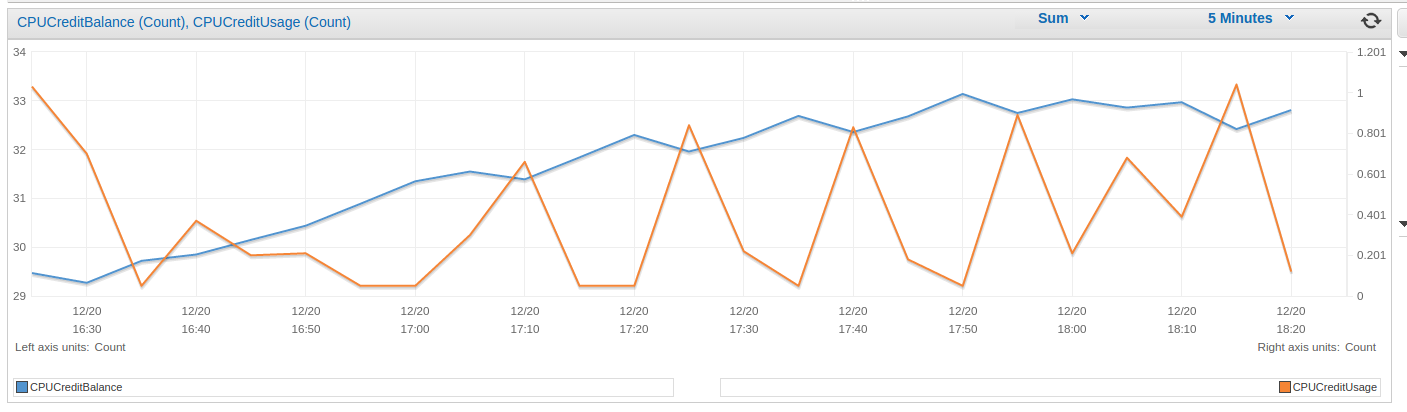

A note about t2 instances and CPU credits

t2-type instances have variable CPU performance, limited by CPU credits which allow the instance to have increased CPU usage for a limited period of time. The t2.micro instance type can use up to 10% CPU consistently without consuming CPU credits.

Ordinarily variable CPU performance wouldn’t be desirable for a load balancer, however HAProxy is very efficient in terms of CPU and these tests show that CPU usage rarely exceeds 10% before being limited by network capacity.

Below is a graph of CPU credit usage and balance over the course of my tests:

As you can see the trend is generally positive, so if you’re not running at the limit of your capacity the whole time you’d probably never run out of CPU credits.

What about small responses?

Previously I was trying to emulate a relatively large response body, such as a full HTML page. But what if you’re trying to load balance something like an API which only returns short JSON strings, would networking still be the limiting factor?

I also ran some tests using this scenario:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

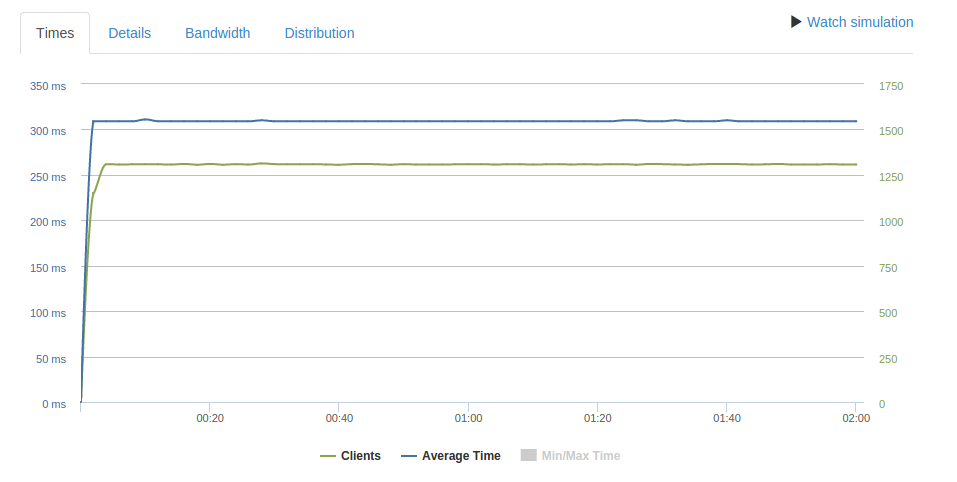

When I tested this with 1000 req/sec HAProxy health checks began to fail on the app servers even though CPU usage was low, this caused response times to jump and fluctuate:

Given that my aim is to benchmark HAProxy rather than the app servers I didn’t bother to debug this and added two additional app servers instead.

After adding the servers I was still experiencing wild fluctuations and timeouts:

Having said that, at 460 req/second it does seem significantly more stable than the larger response size:

It seems that the limit of the t2.micro is around 500 req/second even for small responses.

What about a c3.large HAProxy instance?

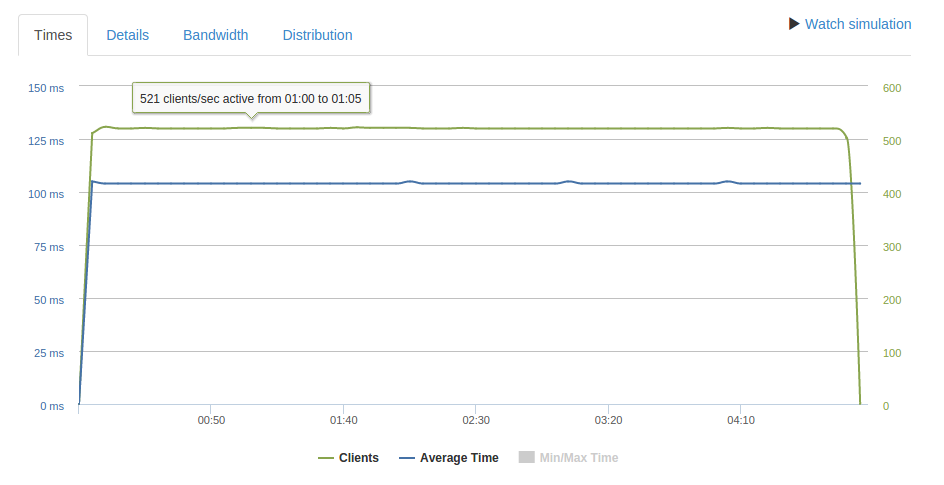

While the focus of this blog post is on the t2.micro, I couldn’t help my curiosity and decided to try a c3.large HAProxy instance with 1000 req/second. As you can see there’s no such problems:

I did see some timeouts at 1500 req/second, although I didn’t bother to create a HVM instance with enhanced networking enabled. The networking performance of the c3.large is described as “moderate” as oppose to “low” in the case of the t2, so an increase of more than double between low and moderate without enhanced networking isn’t bad.

Conclusion

You should be safe to run a t2.micro for your HAProxy instance if you’re performing less than 400 req/second and 180 Mb/second. If you’re likely to be running close to this limit most of the time you may want to consider running a larger t2 instance to avoid running out of CPU credits.

If you need to go larger then a c3.large should be good for 1k/second, although I suspect an m3.medium would probably perform similarly too.

In any case, you’re probably going to run out of network capacity before you hit CPU limits regardless of what instance you choose.